Saamir Nizam

May 14, 2020

Litigation and the Power of Mentorship

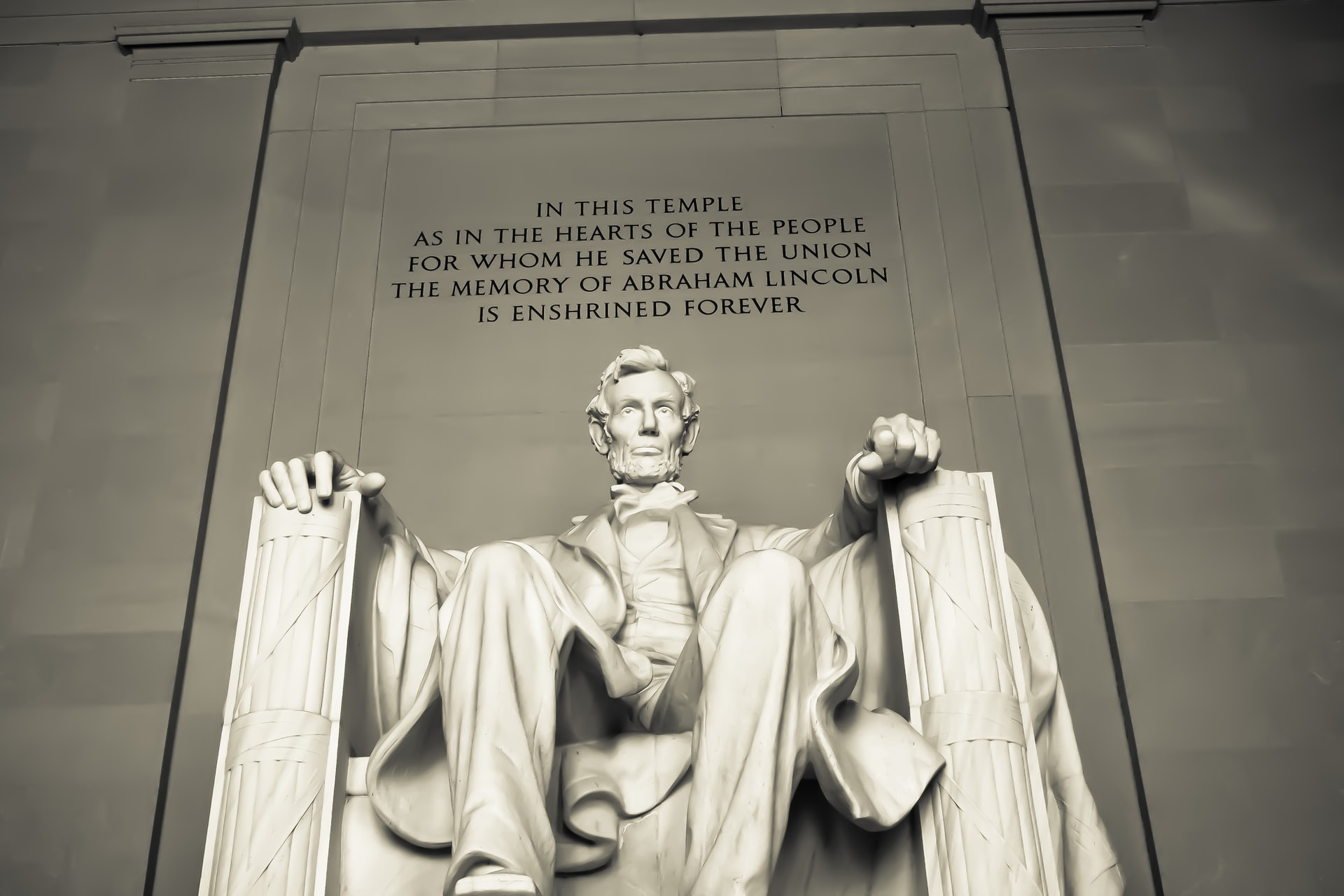

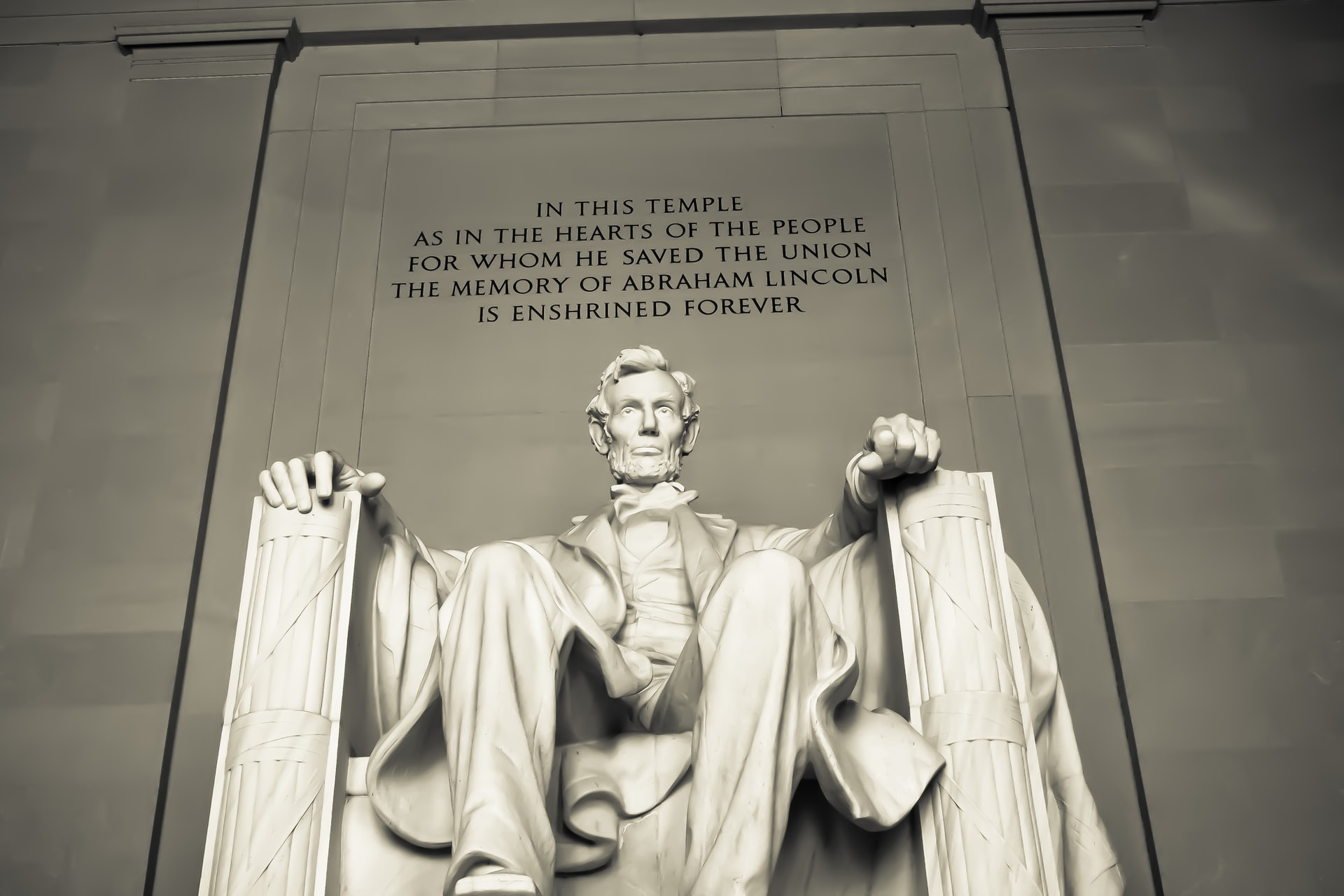

In law, as in life, there’s no better place to start than with the 16th President of the United States.

Abraham Lincoln was a storied and formidable courtroom lawyer long before he became president. Despite his renowned skills as a litigator, Lincoln gave sound legal advice to avoid going to court whenever feasible. This is shown in the story of when an existing client came to him in a rage, insisting Lincoln bring a lawsuit for $2.50 against an impoverished debtor. Lincoln tried to dissuade his client, but the man was determined upon revenge. When he saw that the creditor was not to be put off, Lincoln asked for and got $10 as his legal fee up front. He gave half of this to the putative defendant, who thereupon willingly confessed to the debt and paid up the $2.50, thus settling the matter to the entire satisfaction of the irate plaintiff.

My mentor was an avid, amateur historian, especially on Lincoln and the Civil War, and a prolific Supreme Court litigator. He was gifted with frightening intelligence, rigorous self-discipline, and an abundance of humility and good judgement, characteristics almost never found together in one person. Aside from two degrees from Harvard and a double Supreme Court clerkship, one had to deal with the former federal prosecutor’s photographic memory. It was the most humbling experience of my life, working for him. Despite all my shortcomings, he was always patient, kind and generous with his time and advice both about law and life. That was also his manner with everyone else, but as his principal legislative deputy, I benefitted with years of daily contact and a shared office with him.

One of our cases is a good and useful example in a short essay on litigation. We were involved in a federal case at the trial level which was testing a statute which my team and I had drafted in the early stages. At the trial level, we were engaged in a vigorous struggle with the opposition, a large, national union which was arguing that the statute had unlawfully deprived them of property without due process of law in violation of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution. On behalf of the Government, we filed a motion to dismiss pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure on the grounds that the complaint failed to state a claim upon which relief could be granted. The case was more complicated, but that is the core of the dispute.

In the two months or so that we researched, drafted the motion and prepared supporting papers, responded to the opposition, and argued it in federal district court, I bore witness to a master applying his craft. I will summarize here what I saw him do:

- Arrive at the office by 6am every weekday, and 9am on weekends, to read the relevant cases and statutes. He would be there late, until 9 or 10pm during the week and 4 or 5 on Saturdays and Sundays. This was one of dozens of cases and legislative matters we were busy with, but extra time had to be allocated for this case because it was conceivably heading to the Supreme Court.

- He made notes in the photocopied pages of the cases, connecting them to other cases and portions of the motion I was drafting in the first instance.

- While I drafted the motion to dismiss on the computer, he sat and drafted the legal brief (memorial) in support of the motion to dismiss on long yellow legal pads, never looking at the cases, but noting their full names and citations.

- Our amazing legal secretary (may you all be blessed with such a talented and patient colleague), deciphered and typed out the handwritten brief in support of the motion, a Herculean task by any measure if you knew his handwriting.

- Without looking, he passed the draft to me to check for correctness. I am not akin to Salieri in talents, but to read my mentor’s writing must be how Salieri felt when listening to Mozart’s ‘Requiem’. Every word, every sentence, every paragraph elegantly composed, delivering not merely a persuasive argument for our position, but a determinative one, where the judge has no choice but to agree. I considered it a game-winning victory if I could find a small morsel of a mistake, thereby making a contribution to the final product.

- He read and revised again and again, teasing out the nuances and perfecting the clarity and delivery of the legal brief, which I had the privilege to file in court.

- On the weekend before the oral hearing on the motion, I was assigned the task of acting as judge, to probe the logic and structure of the argument, the relevance of the case law, the basic details contained in the documents of the case (a motion to dismiss only tests the law and does not test the facts of the case because discovery – interrogatories, depositions, other fact-finding – has not concluded). At the end of those four or five full mock sessions, at 30 years his junior, I was exhausted and he looked like he was just getting warmed up.

- On the day of oral argument, he dressed in his usual suit, button-down white shirt, and academic striped tie. At the podium he did not deliver an argument, but more so engaged in a conversation with the judge, who was younger than him and considered one of the best on the federal bench (and is now a Supreme Court justice). Both had obviously read the briefs on each side, but the conversation was about the interaction of the cases cited in the brief, what those cases said, what they meant, and how they applied in this dispute. The judge kept casually setting traps, cul-de-sacs which would mean a certain loss for our motion. The traps were respectfully and thoughtfully avoided, while impressing on the court the dangers, risks, and costs of allowing the case to proceed to trial. Everyone who was there that day recalls it as a study in sublime oral advocacy.

In the weeks that followed, we were busy with other matters (principally, the impeachment of President Clinton), but both anxiously awaiting word of the court’s ruling on our motion. When I received the call from the court’s clerk that the slip opinion of the decision was available, I rushed to get a taxi to court. I was still in the courthouse, when my mentor called on my cell-phone and asked me to read the decision to him. While navigating the court’s security, hailing a cab, and the ride back to the office, I read to him the court’s decision and reasoning – we had prevailed. It was satisfying, but we both agreed back at the office that this was just the first skirmish. There would be – and there was – an appeal to the Federal Court of Appeals, a further appeal to the en banc panel of that Court, before the case went to the Supreme Court. Parenthetically, we prevailed in every court, but after filing our opposition to the plaintiff/applicant’s application for leave to appeal to the Supreme Court, the union and the Government settled the dispute, mooting the appeal. One day, I saw a note from the opposing lawyer, a renowned court litigator herself, thanking my mentor for the experience of arguing a case against him and his gentlemanly manner in and out of court.

What are we to take from the lessons above? Much, I suspect, but at a minimum: negotiate to settle a dispute as inexpensively as possible – it will make the client happy and they will bring all their potential claims to you. If you have to go to court, count yourself fortunate, prepare intensely, be kind and generous to all while vigorously defending your client. And remember the advice your mentor(s) gave you.

At our last meeting in the same federal courthouse for lunch now over a decade ago, he gave me his last piece of advice, characteristically quoting Mark Twain: “Live a life so honorable that at your passing even the undertaker will be sad.” Abe Lincoln would have appreciated that wisdom.

My mentor and I also shared a common passion for baseball. Perhaps in the future, I will say a few words about the strong bond between good advocacy and baseball.

Edinburgh,

5 May 2020

Saamir K. Nizam

Saamir is a Solicitor and Notary Public in Scotland and Foreign legal counsel at Đukić Novaković Law firm advising the firm in a variety of litigation matters including contract disputes, debt recovery, corporate due diligence, UK/EU competition, white-collar regulatory investigations, and international law.

Read more from our authors: